What You Should Know About 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome

In this video, we learn about Parker, who has experienced heart failure and developmental delays due to 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. His mother, Lauren, shares her experiences trying to determine the cause of the various health issues of her son.

Eventually, they learned Parker was missing his thymus. A nurse practitioner mentioned this is a big indicator of a genetic condition called 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, also known as DiGeorge syndrome. This prompted genetic testing where they determined Parker has 22q11.2 deletion syndrome.

What is 22q11.2 deletion syndrome?

This syndrome is caused by a missing piece of chromosome number 22, which affects the development of various organs and systems in the body. This genetic change can cause an array of health issues including congenital heart defects, immune deficiencies, hypocalcemia, palatal abnormalities, and developmental delays, and behavioral and learning differences.

All cells in our body contain thousands of pairs of genes. Genes are the instructions that tell our bodies how to grow and function. We can think of genes like chapters in books, and the books are called chromosomes. We typically have a total of 46 chromosomes, arranged into 23 pairs.

Why is it important to identify 22q11.2 deletion syndrome during pregnancy?

A diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome is not always obvious during pregnancy or after the child is born. The average age of diagnosis after birth is 4 years old. Early prenatal screening for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome assists healthcare providers to offer treatment and management strategies that are meant to improve health outcomes for a child affected with the condition, starting at birth.

Early diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome helps healthcare providers to:

- Minimize seizures by treating low calcium levels early

- Identify palate abnormalities to help breathing, feeding, and speech

- Customize care strategies for immune deficiencies (including vaccine eligibility and cadence of shots), development delays, and learning difficulties

- Consider delivery at tertiary care center and plan surgeries for heart defects

How common is 22q11.2 deletion syndrome?

Recent studies determined the prevalence of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome is approximately 1 in 1524, which was much higher than previously expected. This is even more common than cystic fibrosis (1/2,500).1-12

Who is impacted by 22q11.2 deletion syndrome?

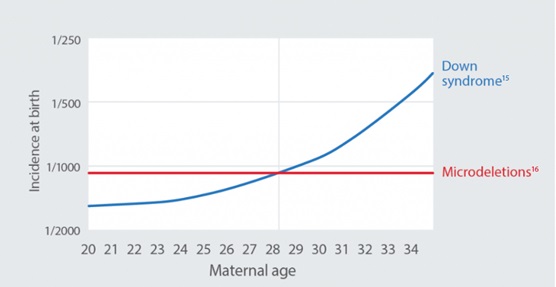

Microdeletions usually occur randomly and are not impacted by age or race of the pregnant individual. A small percentage of people inherit 22q from a parent.13

Microdeletions are more common than trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) in individuals younger than 28 years of age.14

How do I find out if my baby has 22q11.2 deletion syndrome?

A Non-Invasive Prenatal Test (NIPT), like Panorama™, can screen for 22q11.2 and other microdeletion syndromes to help prepare parents before birth. Panorama™ is a simple, safe, and highly accurate screen for common genetic conditions in the baby’s DNA as early as 9 weeks of gestation. Panorama™ analyzes the baby’s (placental) DNA through a simple blood draw from the pregnant person’s arm.

NIPT results indicate if there is an increased chance for the baby to have a condition and whether additional diagnostic testing is needed.13,17-25

- Panorama™ Extended Prenatal Panel screens for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, and chromosomes 21, 13, and 18, monosomy X, Y, and triploidy

- Panorama™ Full Prenatal Panel screens for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, and chromosomes 21, 13, and 18, monosomy X, Y, triploidy and four other microdeletions (cri-du-chat, 1p36 deletion, Angelman, and Prader-Willi)

Learn how to order Panorama™ here.

What if my baby tests positive for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome?

If NIPT results find an increased risk for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, further diagnostic testing (such as amniocentesis) is recommended to confirm if the baby has the condition. It is important to work closely with a healthcare provider to develop a personalized treatment plan. Genetic counselling may also be recommended to understand the condition and its inheritance patterns.13

While there is no cure for 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, there are various treatments and interventions available to manage symptoms and improve quality of life. These may include surgeries to correct heart defects, speech therapy for speech and language problems, and educational interventions for developmental delays and learning difficulties.

At LifeLabs our team of certified genetic counsellors are available to counsel patients and healthcare providers on Panorama™ NIPT, NIPT choices, and/or results at Ask.Genetics@LifeLabs.com or 1-844-363-4357. Services are available from 8am-7pm EST in both English and French. In the case of “High Risk” results, our genetic counsellors reach out to healthcare providers to provide clear next steps to their patients.

For more information about Panorama™ NIPT or to order a test, please visit LifeLabsGenetics.com/Panorama.

1. Dar et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Published online January 13, 2022. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.01.002

2. Maternal age-related risk for common fetal trisomies across pregnancy. UpToDate. Accessed January 20, 2022. https://www.uptodate.com/contentsimage?imageKey=OBGYN%2F75423

3. Martin et al. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021 Apr; 70(2):1-51. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:100472.

4. Hamosh et al. J Pediatr. 1998 Feb; 132(2):255-9.

5. O’Sullivan, Freedman. Lancet. 2009 May; 373(9678):1891-904.

6. Prior et al. Spinal muscular atrophy. In: Adam et al, eds. GeneReviews. University of Washington; 2000.

7. Palmer et al. Am J Med Genet A. 2018 Apr; 176(4):936-44.

8. McDonald-McGinn et al. 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. In: Adam et al., editors. GeneReviews. University of Washington, 1993- 2022.

9. Norton et al. Perinatal and genetic outcomes associated with no call cfDNA results in 18,497 pregnancies, SFMS’s 40th Annual Pregnancy Meeting 2021

10. Cheung et al. Genet Med. 2014 Jan; 16(1):40-4.

11. Grand et al. Am J Med Genet A. 2018 Oct; 176(10):2167-71.

12. Palmer et al. Am J Med Genet A. 2018 Apr; 176(4):936-44.

13. Natera 22q Counselling Aid NAT_OS_22qCounselAid_20220110_NAT-8020768

14. Modified from Hook EB. Chromosomal abnormalities: prevalence, risks and recurrence. In Prenatal Diagnosis and Screening. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone 1992; 351-392. & Hook EB, et al. Rates of chromosome abnormalities at different maternal ages. Obstet Gynecol:1981, 58(3);282-5.

15. Snijders RJ, et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Mar; 13(3): 167–70.

16. Combined prevalence using higher end of published ranges from Gross et al. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2011; 39:259-266; and from www.genetests.org. Total prevalence may range from 1/1071–1/2206.

17. Stokowski et al. Prenat Diagn. 2015 Dec; 35(12):1243-6.

18. Jones et al. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Feb; 51(2):275-6.

19. Hooks et al. Prenat Diagn. 2014 May; 34(5):496-9.

20. Schmid et al. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2018; 44(4):299-304.

21. Bassett et al. J Pediatr. 2011 Aug; 159(2):332-9.e1.

22. Cheung et al. Genet Med. 2014 Jan; 16(1):40-4.

23. Grand et al. Am J Med Genet A. 2018 Oct; 176(10):2167-71.

24. Palmer et al. Am J Med Genet A. 2018 Apr; 176(4):936-44.

25. McDonald-McGinn et al. 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. In: Adam et al., editors. GeneReviews. University of Washington, 1993- 2022.

26. www.22q.org.

27. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1330.

28. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1144.

29. Niebuhr, E. The cri du chat syndrome: epidemiology, cytogenetics, and clinical features. Hum. Genet. 44: 227-275, 1978.

30. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1191.